Parts needed

- B&W Tek BTC-110S (used - ebay)

- RS232 to USB Cable

- 5V 3A DC Barrel Jack

- Gas-discharge (CFL, Mercury-Vapour) or Calibration Lamp

First Steps

Powering on

The B&W Tek BTC-110S is surprisingly still one of the more broadly available spectrometer units that can be bought used for a reasonable price, despite its age.

- If they don’t fit (at all): sand down the holes evenly, clean and try again.

- If you notice any play: size down the holes (ONLY IF FUSION FILE IS PROVIDED) or adjust print settings. I prefer using random seam positioning whenever other options are unavoidably interfering with the inner diameters of accurately sized holes, for example.

[When sanding PETG-CF or any carbon fibre filament wear at least a surgical mask, as the tiny fibres are harmful to your lungs and will most likely accumulate.]

Step 1

A bit of history

The B&W Tek BTC-110S is surprisingly still one of the only more broadly available spectrometer units that can be bought used at a reasonable price, despite its age. From what can be gathered online, it was originally installed inside a “Carotenoid Antioxidant Scanner” (NuSkin Pharmanex S3 BioPhotonic Scanner), a somewhat shady product by a large MLM-company that sold, among others, pricey skincare products. Surprisingly though, at its core it was likely a legitimate Raman spectrometer. Whether or not their final product was a shameless attempt at using fancy science equipment to make dishonest claims, doesn’t matter to us, since we only have one part of the original assembly anyway, the spectrophotometer – and it is very much functional!

Step 1

Intro

In simple terms, a spectrometer – or spectrophotometer – is an instrument that lets you measure light. It allows us to determine how much of a given wavelength is present in the light signal being fed into the entrance slit. Similar to a prism, the entering light is split up into its constituent wavelengths – though here a diffraction grating is used to split it much more precisely – and by that reflected onto a light-sensitive sensor-array to calculate and digitize a relative intensity.

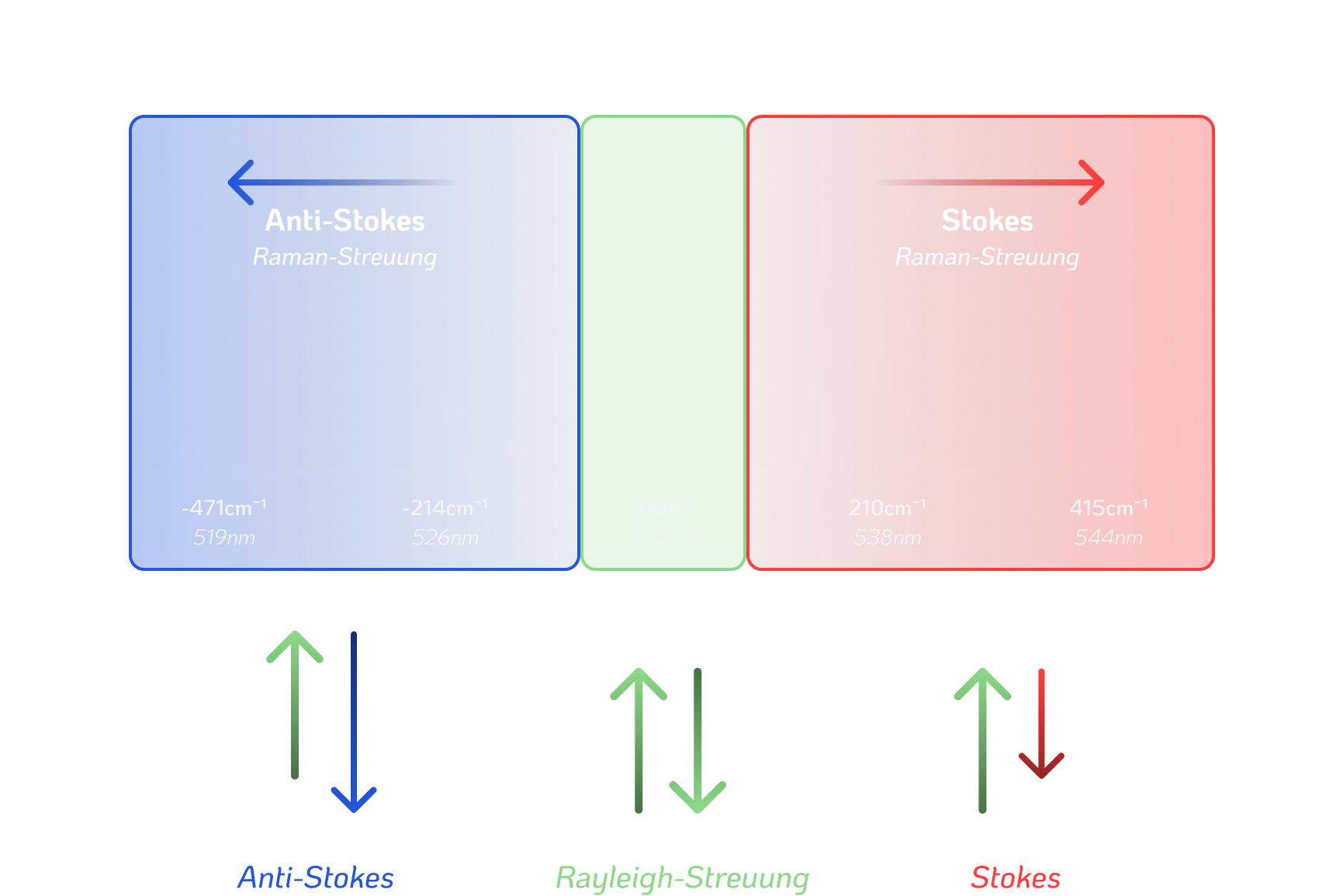

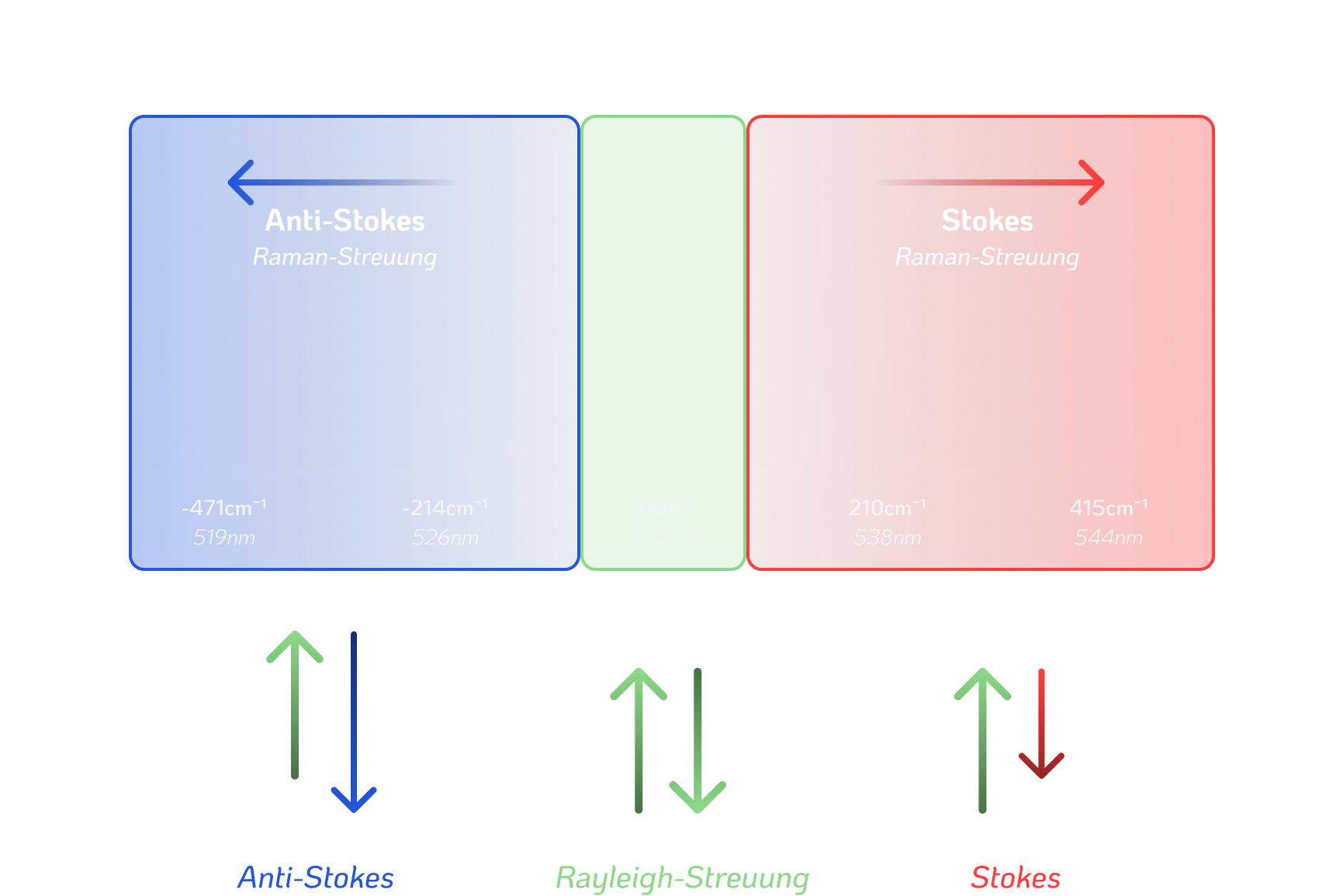

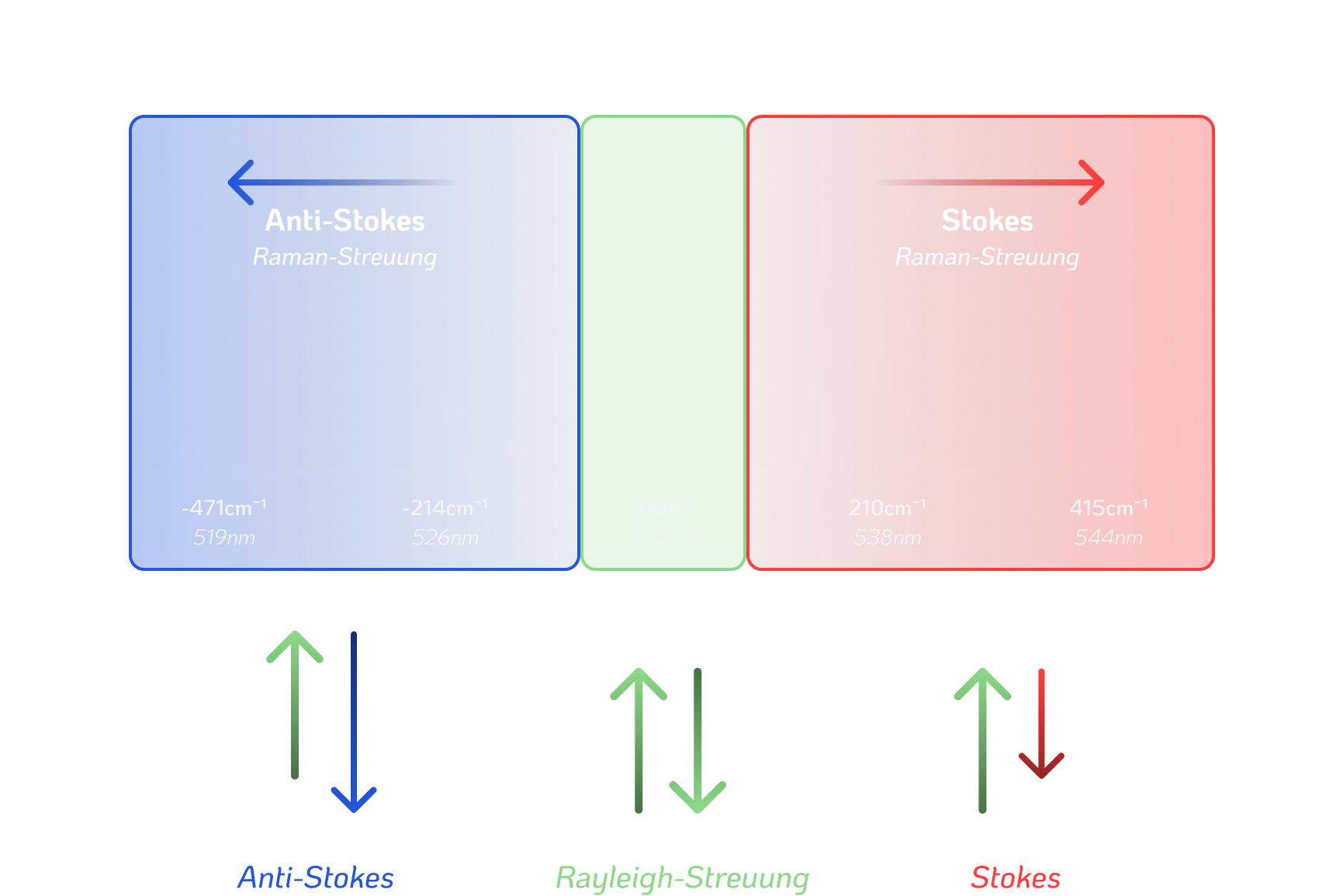

The spectrometer unit allows you to plot the receiving signal onto a 2-axis graph consisting of wavelength on the x-axis and a respective, arbitrary intensity value on the y-axis. The wavelength range of the device lies between 400-725nm, with its intended operating range at 400-580nm. This covers the visible spectrum quite nicely, but also isn’t necessarily important for our purpose, since most of the Raman-shift of our interest occurs between the excitation wavelength of 532nm and somewhere up to a maximum of 600nm in the Stokes region. Since this project uses a longpass filter, which lets wavelengths above – in our case 550nm – pass and block everything below, it becomes obvious that resolution is more important than a broad spectral range. Now it might seem evident that it likely lacks a portion of the Raman-signal, which lies between the laser’s wavelength of 532nm, and the filter cut-on at 550nm. But this isn’t as significant as it seems at first. Roughly speaking, at worst, this setup captures the first signals at a shift of 600cm^-1. Most molecular groups display characteristic activity and thus Raman-shift somewhere between 450-1650cm^-1 so it is still very capable at identifying compounds!

Step 1

Cleaning & 3D-Printing

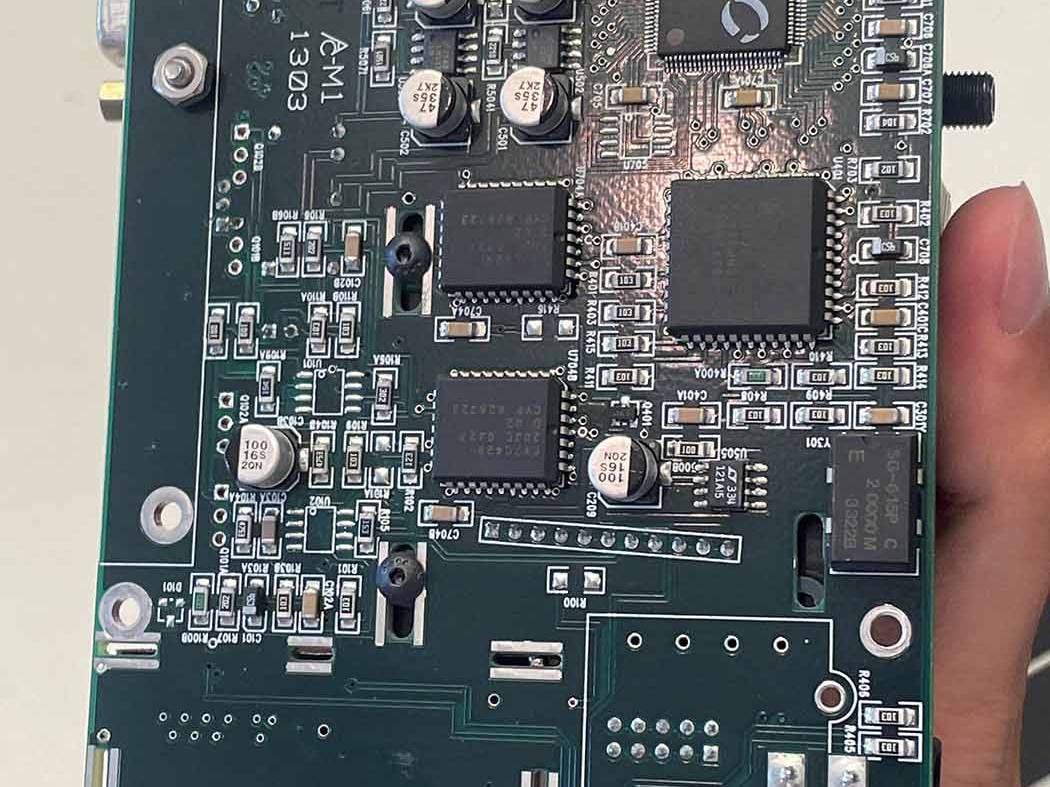

Upon receiving your spectrometer unit, carefully dust off the entire PCB and the fan using a small hand-blower usually used for camera lenses or even better, inert compressed gas. Proceed to clean the rest by using a cloth dampened with 99% alcohol and cotton tips.

Afterwards, I highly advise putting the whole unit inside a small enclosure to protect the sensitive electronics and the PCB from environmental factors. For this I modelled a crude housing, that is far from ideal but gets the job done. If you decide to make your own, the following image shows the essential dimensions. Make sure to leave some venting holes to ensure sufficient airflow for the cooling-fan, as it pulls outside air onto the cooling block.

Step 2

Acquiring a Spectrum

Now, to acquire the first spectrum of the visible light, like a lamp, screen, or sunlight, we first connect the spectrometer using the 5V barrel connector. It uses a thermoelectric cooling element in combination with a fan and heat sink to cool down the sensor initially and continuously. Practically this means that for the sensor to work most efficiently, it is best left for 10 minutes after powering on. This warm-up – or rather cool-down – period is crucial for the accuracy of the sensor. Keep this in mind for when you inevitably encounter this, by starting the continuous acquisition immediately after plugging in. The difference will be noticeable immediately: there is a lot more background noise and seemingly random spikes keep interfering until it eventually stabilizes.

This is the original software, which was kindly reuploaded on another blog. I also created a more contemporary acquisition software that offers the same features and more, but to avoid any unknown errors and ensure the communication works, it’s best to use the original at first.

At this point, connect the RS232 adapter to both the spectrometer and your device. The software should initialize as soon as it establishes communication. If it doesn’t pop up immediately, press “Detect Spectrometer” in the navigation bar and it should initialize with the blank graph layout. Now navigate to the settings menu, displayed as an icon on the very right of the toolbar. The window titled “Calibrate” pops up and offers some guidance. This is where the wavelength calibration will take place later on, but for now set the “C1” value at the bottom from 0 to 1 and press Ok. Now the spectrometer should be operational, so test it by starting an integration or scanning continuous. In the toolbar on the left, at the very bottom, there is a bright green arrow on a graph. This opens a submenu where you can both capture and clear the background spectrum. Now is the time to play around a bit to familiarize yourself with the software.

The integration time can be thought of as the shutter speed on a camera and is usually set to 50ms for alignment testing, or somewhere between 3000ms and 20000ms for Raman spectroscopy. The averages determine, even when pressing “Scan Once”, the number of acquisitions to be taken and averaged. During this process, it displays the most recent scan, until the final one, after which it quickly presents you with the averaged and background subtracted spectrum. The background noise, in the case of just using the spectrometer to view different light sources, is best captured by blocking the input with your finger. This way you only acquire the noise of the digital sensor, which can then be captured using the option in the left toolbar. Until you clear the background, it will always be subtracted from the subsequent scans. Keep in mind that when you’re changing the integration time, the background should be acquired again – the program doesn’t tell you that or clear it, which is why I implemented it in my software.

[As discussed here, certain adapter chipsets are incompatible with operating systems other than Windows or virtualization methods. I bought a cable by Ugreen, which was readily sold on Amazon for 15$.]

Step 3

Wavelength Calibration

The calibration step is an important one, and assigns a wavelength to each pixel index value being displayed on the x-axis currently. For this, a light source of known wavelengths is used and a pixel number assigned to, at least, four of the most identifiable peaks and their respective, known wavelengths. This is a crucial step to eventually achieve properly scaled Raman spectra. For rough identification, even poor calibration will yield a useful result, when comparing a known substance to a reference, for example. In contrast to the very precise optical alignment required later on in the process, this is one of the more forgiving steps – and also an easy one to achieve good results at.

Although there are calibration lamps for several thousand dollars, gas-discharge lamps provide a solid, reliable alternative. Ideally, a mercury-vapor lamp is used as a cheap and well documented source of known spectral lines. Any CFL will probably also work, as long as you can make out distinct peaks and the wavelengths lie closely to the range of interest at 550nm. In that case, most of the prominent spectral lines are, most likely, also emitted by the mercury vapour content and the phosphors inside. I positively tested both a calibration lamp from an astronomy shop, as well as a used mercury bulb for 20$, including ballast.

To get started, first acquire the background spectrum and assign it in the software. The integration time isn’t crucial, as long as you receive a clean spectrum with prominent peaks. Turning off any other light source during acquisition is good practice at this point. Depending on the calibration source chosen, you can now look up the corresponding spectrum, along with the wavelengths at its most characteristic peaks. For mercury-vapour, the spectral lines and their respective wavelengths are also listed on Wikipedia.

To identify the exact pixel number, the software provides a simple cursor functionality. It can be found two spots above the background subtraction in the left toolbar. This allows you to drag a vertical line from the very start of the x-axis onto the points of interest. Write down the pixel number of the known peak, along with the referenced wavelength. For the calibration to work, a minimum of four calibration points is needed – the more the better.

After having identified all characteristic peaks and writing down the values, head over to the settings menu in the top right. Navigate to the second tab “Least-Squares Fitting” and fill in all the pixel values and the respective wavelength. It will then automatically calculate your final calibration variables. Take a screenshot or write them down next to the calibration values for future reference. Click Ok and take another scan. The pixel number on the horizontal axis should now be replaced by wavelength. To roughly verify the accuracy, shine a green laser slightly into the spectrometer, avoiding oversaturation of the sensor. Depending on the quality of the laser, it should display a more-or-less distinct peak around 528-536nm. Note that some cheap laser assemblies ship without an infrared-filter, which will quickly flood the sensor and completely oversaturate all of its pixels.

Misc

Upgrade Options

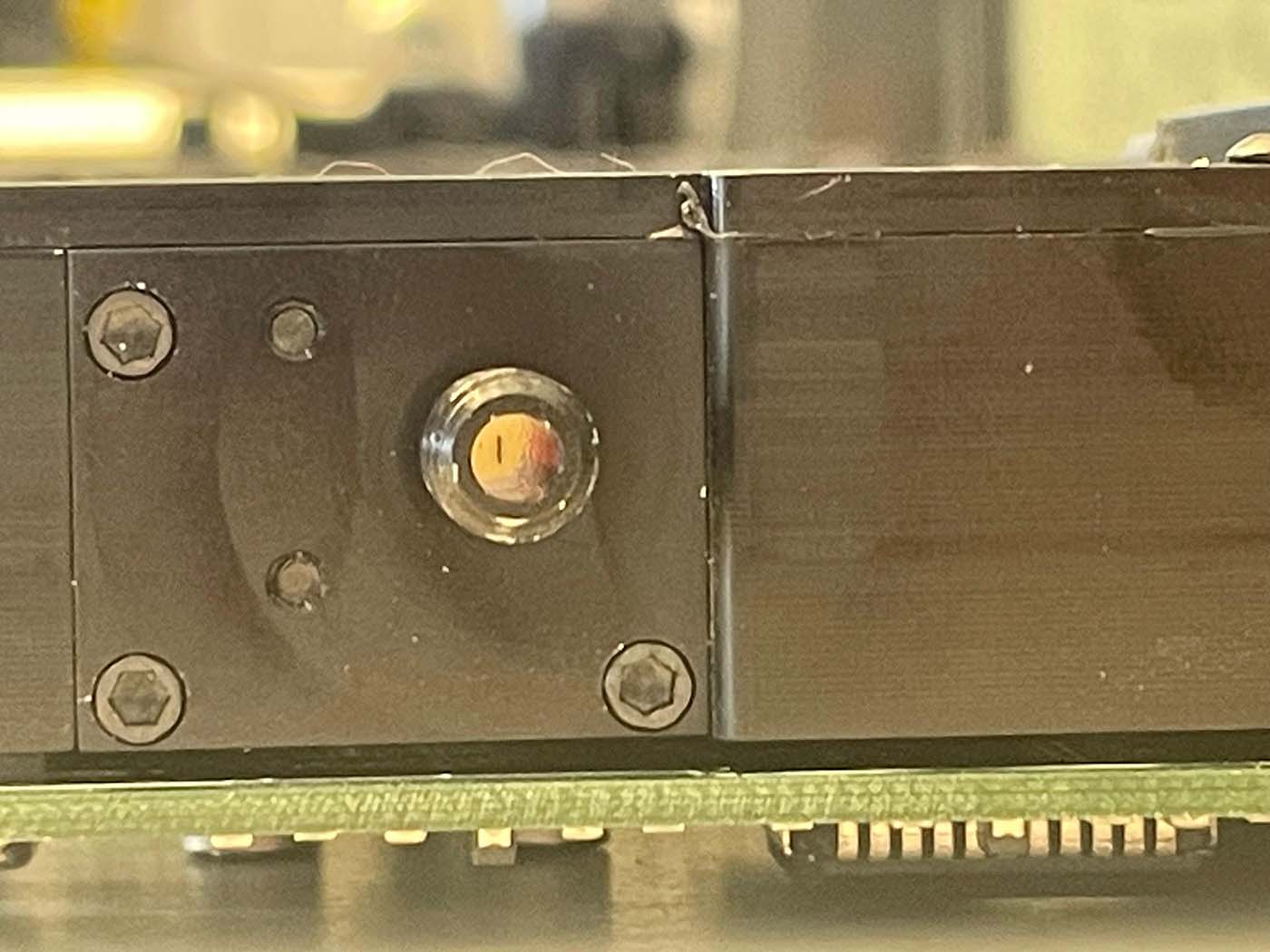

The entrance slit is intended to be fed using a SMA905 optical fibre cable, which is threaded onto the stud. For simple spectroscopy work, this is not necessarily required and can be left out entirely – even for the final Raman assembly! Just know that focusing light into the slit is much easier to achieve, than focusing into a narrow optical fibre core. When testing or even for calibration purposes with broad spectrum light, it is sufficient to roughly point the input at the source. To protect the input slit, which is a tiny piece of glass with a 50um slit at its center, I designed a simple screw-on cover. If you want to model it yourself, the thread providing the best fit – along with some additional clearance – was the ANSI Unified Screw Thread 0.25 in, ¼-36 UNS, easily found in Fusion 360.

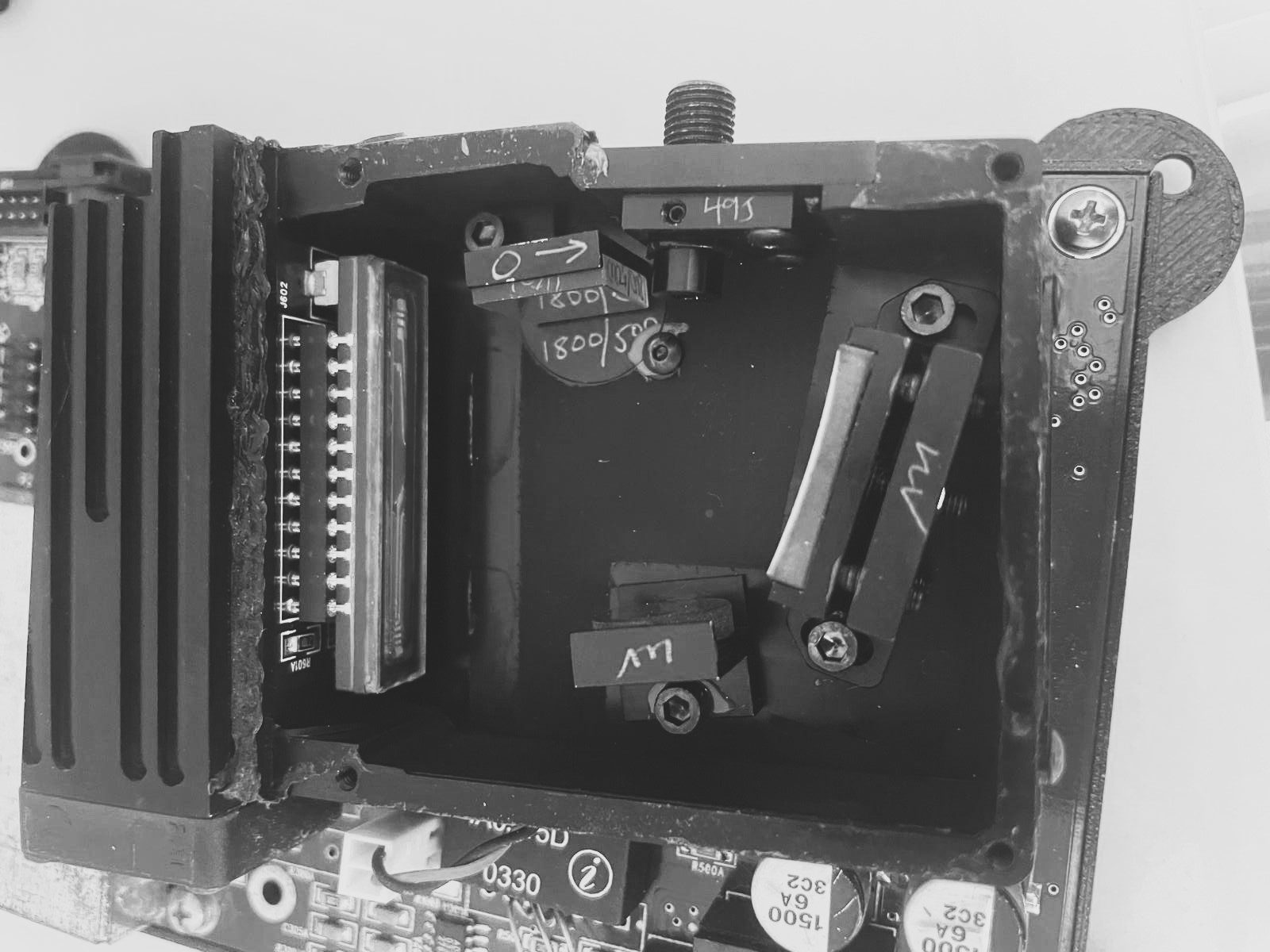

Aligning the mirrors inside the spectrometer’s optical assembly is most often discussed as the first line of action, if you want to increase resolution around your required wavelength range. While this is a good idea generally, in practice it proves to be quite difficult and has the potential to throw off the alignment entirely. If you don’t have any experience, don’t do this before getting some practice aligning the beam path of the final Raman assembly. Out of the box, my unit’s range seemed sufficient, and its limitations only became relevant when eventually capturing the small Raman shifts.

There are various effective upgrade options for the spectrometer itself that will undoubtedly increase its capabilities to a great degree. Most notably the CCD-sensor itself… SEE WHATEVER!!

Replacing the diffraction grating is also guaranteed to provide an increase in resolution, though this can be a difficult endeavour, since any slight misalignment of the optics can render it temporarily unusable. I haven’t done this myself but HERE is a forum discussion talking about it. You have to work in a glove-box ideally, also prevent light from entering, which means you won’t be able to see, and then make tiny iterative adjustments to get everything just right.